Galled by the Gallbladder?

Your Tiny, Hard-Working Digestive Organ

Most of us give little thought to the gallbladder, a pear-sized organ that sits just under the liver and next to the pancreas. The gallbladder may not seem to do all that much. But if this small organ malfunctions, it can cause serious problems. Gallbladder disorders rank among the most common and costly of all digestive system diseases. By some estimates, up to 20 million Americans may have gallstones, the most common type of gallbladder disorder.

The gallbladder stores bile, a thick liquid that’s produced by the liver to help us digest fat. When we eat, the gallbladder’s thin, muscular lining squeezes bile into the small intestine through the main bile duct. The more fat we eat, the more bile the gallbladder injects into the digestive tract.

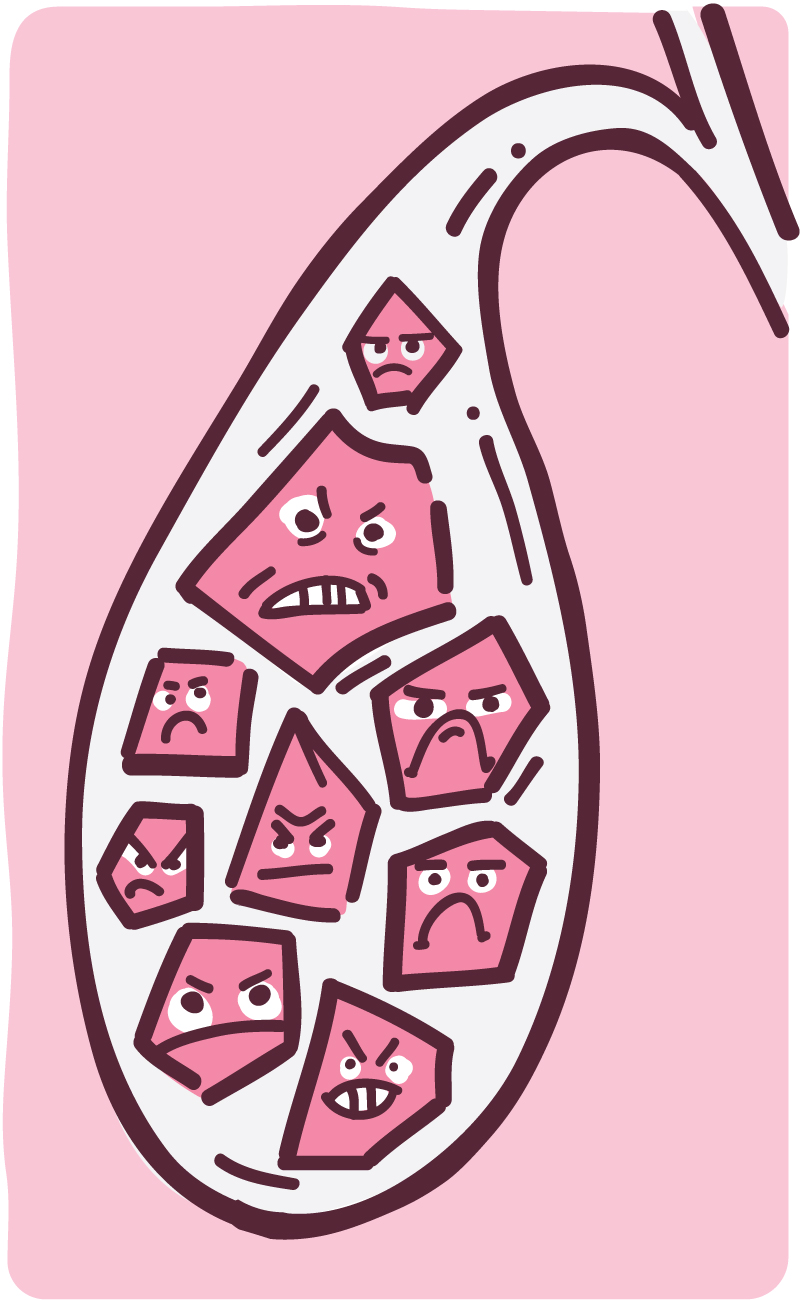

Bile has a delicate chemical balance. It’s full of soluble cholesterol produced by the liver. This is a different type of cholesterol than the kind related to cardiovascular disease. If the chemical balance of bile gets slightly off, the cholesterol can crystalize and stick to the wall of the gallbladder. Over time, these crystals can combine and form gallstones.

Gallstones can range from the size of a grain of sand to that of a golf ball. When the gallbladder injects bile into the small intestine, the main bile duct can become blocked by these crystalline stones. That may cause pressure, pain, and nausea, especially after meals. Gallstones can cause sudden pain in the upper right abdomen, called a gallbladder attack (or biliary colic). In most cases, though, people with gallstones don’t realize they have them.

The causes of gallstones are unclear, but you’re more likely to have gallstone problems if you have too much body fat, especially around your waist, or if you’re losing weight very quickly. Women, people over age 40, people with a family history of gallstones, American Indians, and Mexican Americans are also at increased risk for gallstones.

“For the average person with an average case, the simplest way to diagnose a gallstone is by an ultrasound,” says Dr. Dana Andersen, an NIH expert in digestive diseases.

If left untreated, a blocked main bile duct and gallbladder can become infected and lead to a life-threatening situation. Gallbladder removal, called a cholecystectomy, is the most common way to treat gallstones. The gallbladder isn’t an essential organ, which means you can live normally without it.

Gallbladder removal can be done with a laparoscope, a thin, lighted tube that shows what’s inside your abdomen. The surgeon makes small cuts in your abdomen to insert the surgical tools and take out the gallbladder. The surgery is done while you are under general anesthesia, asleep and pain-free. Most people go home on the same day or the next.

Researchers have long investigated medications that can prevent gallstones from forming, but these therapies are currently used only in special situations.

It’s uncommon for the gallbladder to cause problems other than gallstones. Gallbladder cancer is often difficult to treat, as it’s usually diagnosed at an advanced stage. But such cancers are relatively rare.

While the gallbladder may not be the star of the digestive system, it still plays an important role. Treat it well by maintaining a healthy diet and getting regular exercise, and the little bag of bile should do its job. Don’t ignore pain or symptoms, and see your doctor if you’re in discomfort, especially after eating.

NIH Office of Communications and Public Liaison

Health and Science Publications Branch

Building 31, Room 5B52

Bethesda, MD 20892-2094

Contact Us:

nihnewsinhealth@od.nih.gov

Phone: 301-451-8224

Share Our Materials: Reprint our articles and illustrations in your own publication. Our material is not copyrighted. Please acknowledge NIH News in Health as the source and send us a copy.

For more consumer health news and information, visit health.nih.gov.

For wellness toolkits, visit www.nih.gov/wellnesstoolkits.