Fishing for Clues to Human Health

Tiny Zebrafish Give Big Insights

The difference between a little fish and a human may seem enormous. But in some ways, fish and people are surprisingly similar. That’s why scientists around the world have been studying a striped fish called the zebrafish. These little fish—about an inch or two long when fully grown—have a lot to teach us about human health.

Like us, fish have a spine, brain, heart, gut, ears, eyes, and other organs. Fish and people use similar processes for eating, moving, fighting germs, and more. And fish and people change in very similar ways from a fertilized egg to a developing embryo.

In recent decades, zebrafish research studies have led to important insights about cancer, heart disease, and stroke. They’ve also shed light on conditions like anxiety and autism. Zebrafish have even helped scientists find and test potential new drugs.

“Zebrafish are a good model for humans in many ways,” says Dr. Brant Weinstein, an NIH expert in zebrafish biology. “We have a lot of the same genes as zebrafish. We have a lot of the same organs and tissues. And we develop in much the same way, using the same Stretches of DNA you inherit from your parents that define features, such as eye color or your risk for certain diseases. genes and processes.”

In fact, zebrafish and people share more than 70% of their genes. So they’re ideal for studying how various genes can affect the health of both fish and people.

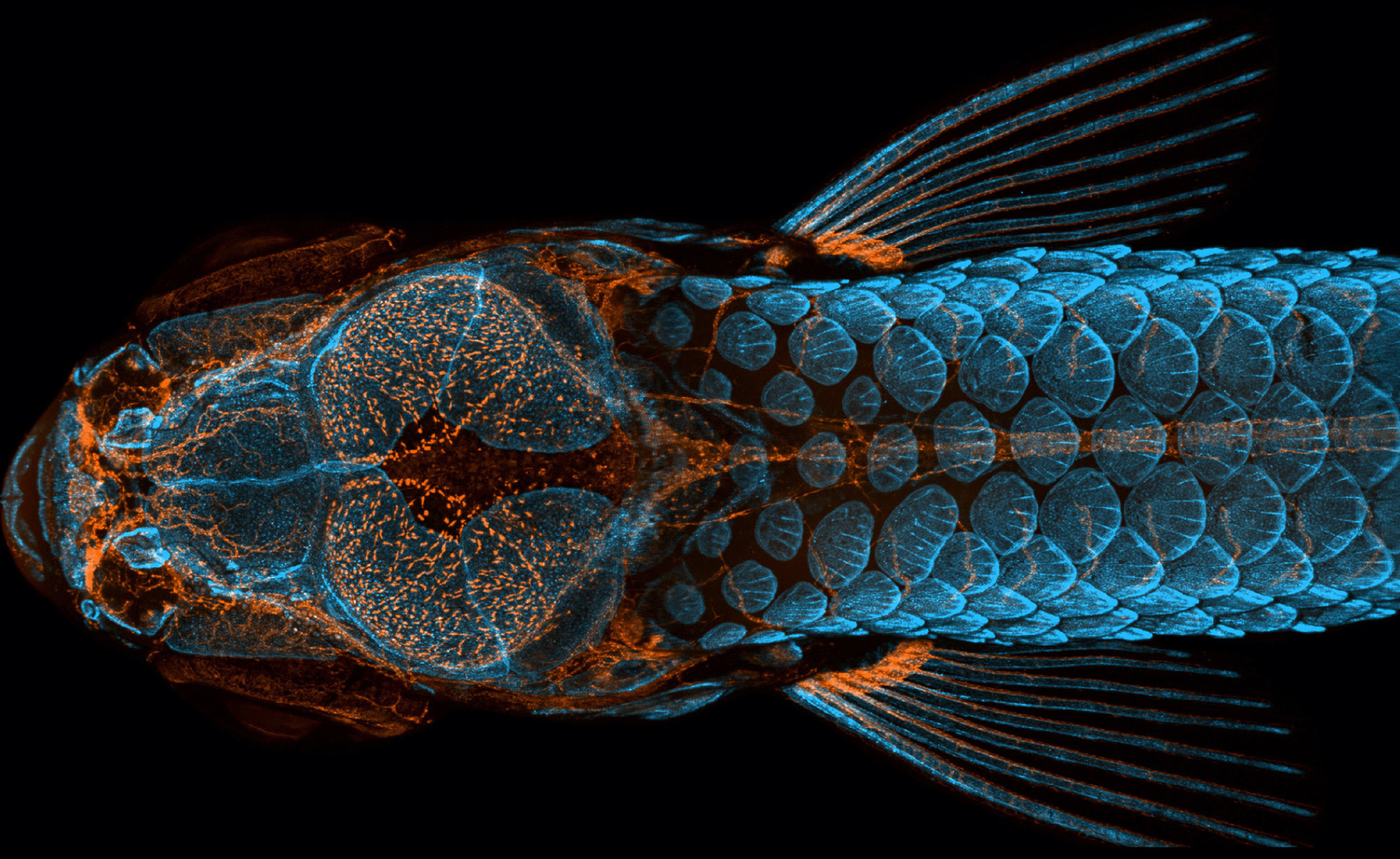

Zebrafish have other traits that are helpful to researchers. They grow up quickly, from a single cell to a free-swimming larval (baby) fish within a few days. And they’re transparent during these early life stages. “You can literally see right through them and watch as all their organs develop,” Weinstein says.

Researchers can add genes that make various Groups or layers of cells that work together to perform specific functions. tissues glow in a rainbow of colors as the fish mature. “The colors make it easy to track how various tissues grow and change inside living animals,” Weinstein explains.

Scientists can even add genes that make living brain cells glow when they’re active, giving new insights into how the brain works.

Unlike humans, zebrafish can regrow damaged limbs and other body parts. Scientists are working to better understand this ability. What they learn could help to improve human treatments for injuries, burns, and even vision or hearing loss.

“If you uncover a process or treatment that works in zebrafish, that’s a good basis for moving forward to see if the same thing also happens in other animals or even people,” Weinstein says. “The fish can give you early evidence that you’re on the right track—that a particular therapeutic approach might be useful.”

Weinstein and his team study the basic biology of blood vessels. Blood vessels can play roles in heart disease and cancer, because tumors can’t grow without a blood supply. The researchers found a way to block key proteins that fuel the growth of new blood vessels in zebrafish. Then they showed that blocking those proteins in mice could reduce tumor growth. These findings suggest new ideas to improve cancer treatment.

It’s important to uncover such basic processes that are essential to life, even if it doesn’t immediately lead to a new treatment or cure. “We don’t always know where new findings in zebrafish might lead,” Weinstein says. “But they lay the foundation for future discoveries that can improve human health.”

NIH Office of Communications and Public Liaison

Health and Science Publications Branch

Building 31, Room 5B52

Bethesda, MD 20892-2094

Contact Us:

nihnewsinhealth@od.nih.gov

Phone: 301-451-8224

Share Our Materials: Reprint our articles and illustrations in your own publication. Our material is not copyrighted. Please acknowledge NIH News in Health as the source and send us a copy.

For more consumer health news and information, visit health.nih.gov.

For wellness toolkits, visit www.nih.gov/wellnesstoolkits.