Q&A

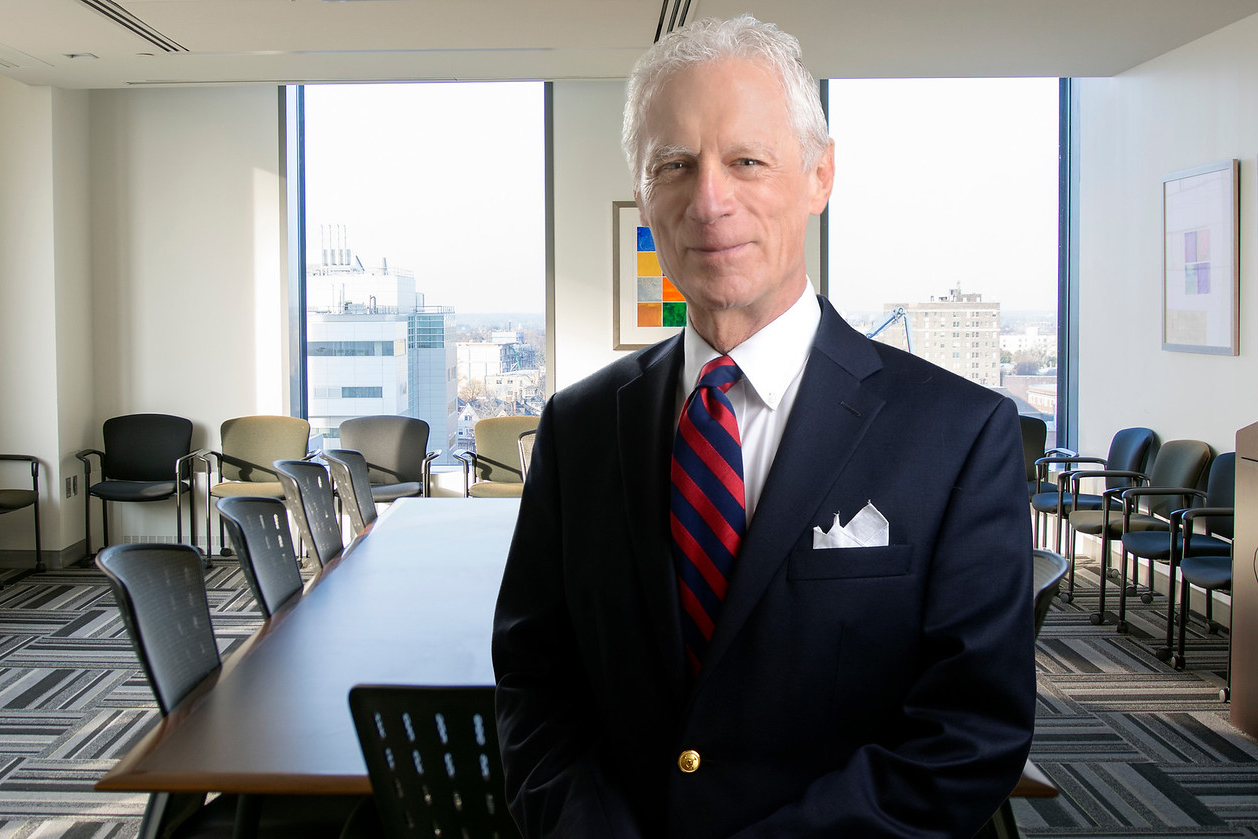

Dr. Leonard Epstein on Family-Based Obesity Treatments

Excerpts from our conversation with Dr. Leonard Epstein, a psychologist who specializes in health behavior change at the University at Buffalo.

NIHNiH: Why are family-based treatments important?

Epstein: Obesity occurs within families, across generations. I believe the most effective treatment involves simultaneously targeting the parent and child for behavior change and weight loss. This has benefits for both the child and parent, with a strong correlation between child and parent (and sibling) weight change. This approach is also more cost-effective than treating the child and parent separately by different health care professionals.

A pediatrician can tell the parent, ‘don’t bring in junk food’ or ‘make sure your kid is not eating it,’ but if the parent is not changing, it’s going to be very difficult for the child. If the parent tells the child ‘don’t eat this ice cream,’ and they’re eating a chocolate bar, the kid is not going to follow.

Our family-based treatment program is based on kids mastering certain skills, like their ability to self-monitor their dietary intake and their activity levels, and to set goals and meet goals. There are also parenting goals: Praising the child for healthy eating. Praising the child for being more active. We do not want the parent to be the food police.

Policing is when a parent asks, “Did you eat that food? Did you do this today? I saw you eat an ice cream cone. Why did you do that?” That kind of parenting in the long run doesn’t work—we’ve demonstrated that in other studies. As opposed to having only healthy food around, and when the child chooses a healthy food because all the food’s healthy, then the parent praises them. Then the child feels empowered because now they’re making a positive choice. The parent is happy. The child is happy because the parent is happy. It strengthens the parent child bond, and it strengthens the positive behavior.

NIHNiH: What are some of the challenges for preventing childhood obesity?

Epstein: We know that kids get heavier throughout childhood. As kids grow, they eat more food. When kids are really young, they don’t have any forward thinking at all. It’s all immediate gratification. But as they get older, they develop more of an ability to understand that maybe I shouldn’t do something now, but I should wait for the better, later benefit.

All prevention is based on engaging in a behavior now for future benefits. Kids are developing that skill throughout their life. It doesn’t fully mature until the early 20s. Food is automatically reinforcing. You eat a donut or something sweet, and you feel good right away. Exercise that kids do on the playground is also highly reinforcing. It’s a lot of fun. But when you start getting into sports and higher level things, you have to work at it. Oftentimes, it’s not fun in the beginning until you get a certain level of skill. Then it becomes fun. So you have these foods that are immediately reinforcing for everybody. Then you have these activities that are not immediately reinforcing.

It’s so easy to make a choice of being sedentary versus active—watching TV versus going for a walk. And our environments are set up now to prompt people to be sedentary for people who are not physically active.

If you took two people who were both the same size and you had them go for a walk, the person who’s a regular exerciser would say, ‘Wow, that was fun.’ But the person who isn't an exerciser would say, ‘Oh, that hurt my legs. And, oh, I'm so tired.’ You have to develop tolerance to the unpleasant aspects of exercise in order for the pleasant aspects to shine through.

NIHNiH: How do you get kids to be more physically active?

Epstein: The best predictor of kids’ activity is parental activity. It’s easy for kids to be sedentary if their whole lifestyle, everything they see is inactive. Finding things kids like and being physically active with them—going on bike rides together, going on walks together, all that stuff—will help. And so will having peers who also are physically active. Kids tend to end up with peer groups that are pretty much like themselves.

But, how do you get a sedentary person, whether they’re a kid or an adult, to start finding exercise more reinforcing? That’s something that a lot of people are trying to figure out.

NIH Office of Communications and Public Liaison

Health and Science Publications Branch

Building 31, Room 5B52

Bethesda, MD 20892-2094

Contact Us:

nihnewsinhealth@od.nih.gov

Phone: 301-451-8224

Share Our Materials: Reprint our articles and illustrations in your own publication. Our material is not copyrighted. Please acknowledge NIH News in Health as the source and send us a copy.

For more consumer health news and information, visit health.nih.gov.

For wellness toolkits, visit www.nih.gov/wellnesstoolkits.